Chile’s 9/11: Fifty Years of Literary Resistance

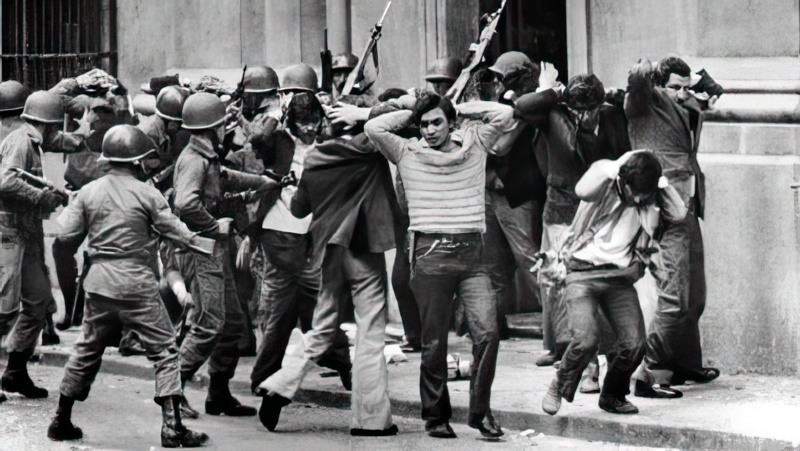

Reflecting upon Chile’s 9/11 September 2023 marks fifty years since the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s socialist government on September 11, 1973. To honor the struggles and sufferings of the Chilean … Read more