In the French Revolutionary Calendar, the Thursday that just passed, May 16, 2019, was Nonidi 27 Floréal, the 237th day of year 227 of the revolutionary era—the ninth day of décade 24 of this year, with Floréal being the eighth month in the French Republican Calendar.

It marked what was the 59th day of the Paris Commune (1871)

101 years ago it was the 237th day of the Russian Revolution!

100 years ago it was the 192nd day of the German Revolution that took place between 1918 and 1923!

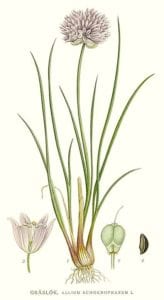

Fête du jour (Feast day of the people on 27 of Floréal): Chives

“The class struggle, which always remains in view for a historian schooled in Marx, is a struggle for the rough and material things, without which there is nothing fine and spiritual. Nevertheless these latter are present in the class struggle as something other than mere booty, which falls to the victor. They are present as confidence, as courage, as humor, as cunning, as steadfastness in this struggle, and they reach far back into the mists of time. They will, ever and anon, call every victory which has ever been won by the rulers into question. Just as flowers turn their heads towards the sun, so too does that which has been turn, by virtue of a secret kind of heliotropism, towards the sun which is dawning in the sky of history. To this most inconspicuous of all transformations the historical materialist must pay heed.” ― Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History

This day that just passed in history.

In 1871.

France. Internationalist gesture celebrated through the Commune. The Vendôme Column is pulled down. The Vendôme Column was erected between 1806 and 1810 in Paris in honor of the victories of Napoleonic France; it was made out of the bronze captured from enemy guns and was crowned by a statue of Napoleon.

The destruction of the column honoring the victories of Napoleon I, topped by a statue of the Emperor, was one of the most prominent civic events during the Commune. It was voted on April 12 by the executive committee of the Commune, which declared that the column was “a monument of barbarism” and a “symbol of brute force and false pride.” The idea had originally come from the painter Gustave Courbet, who had written to the Government of National Defense on 4 September calling for the demolition of the column. In October, he had called for the a new column, made of melted down German cannons, “the column of peoples, the column of Germany and France, forever federated.” Courbet was elected to the Council of the Commune on April 16, after the decision to tear down the column was already made. The ceremony took place on May 16, in the presence of two battalions of the National Guard and the leaders of the Commune, a band played the Marseillaise and the Chant du Départ. The first effort to pull down the column failed, but at 5:30 in the afternoon the column broke from its base and shattered into three pieces. The pedestal was draped with red flags, and pieces of the statue were taken to be melted down and made into coins.

In 1919.

Canada. The Winnipeg General Strike begins. By 11:00, almost the whole working population of Winnipeg, Manitoba had walked off the job. Soldiers returned home desiring jobs and a normal lifestyle again only to find factories shutting down, soaring unemployment rates, increasing bankruptcies and immigrants taking over the veterans former jobs which rose social tensions. The cost of living was raised due to the inflation caused by World War I making it hard for families to live above poverty. Another component which caused the strike was the working conditions of many factories that upset the employees thus pushing them to make the change that would benefit them. Railways in particular were put in the prairie climate and many of the employees were hurt around the mountains due to rock falls and the misuse of explosives. Sleeping there, the workers stayed in tents with unsanitary bunkhouses making it overcrowded.

In 1934.

Minneapolis General Strike. The Minneapolis general strike of 1934 grew out of a strike by Teamsters against most of the trucking companies operating in Minneapolis, the major distribution center for the Upper Midwest. The strike began on May 16, 1934 in the Market District (the modern day Warehouse District). The worst single day was Friday, July 20, called “Bloody Friday”, when police shot at strikers in a downtown truck battle, killing two and injuring 67. Ensuing violence lasted periodically throughout the summer. The strike was formally ended on August 22.

The strike was remarkably effective, shutting down most commercial transport in the city with the exception of certain farmers, who were allowed to bring their produce into town, but delivering directly to grocers, rather than to the market area, which the union had shut down.

The market was to be the scene of the fiercest fighting during the earliest part of the strike. On Saturday, May 19, 1934, Minneapolis Police and private guards beat a number of strikers trying to prevent strikebreakers from unloading a truck in that area and waylaid several strikers who had responded to a report that scab drivers were unloading newsprint at the two major dailies’ loading docks. When those injured strikers were brought back to the strike headquarters the police followed; the strikers, however, not only refused to let the police into the headquarters, but left two of them unconscious on the sidewalk outside.

In 1969

USA. May 15, May 16 and beyond. Battle for People’s Park

Riots and protests continue following brutal suppression by police and military of People’s Park in Berkeley, California on May 15, 1969. This week is the 50th Anniversary.

Beginning at noon on May 15, about 3,000 people appeared in Sproul Plaza at nearby UC Berkeley for a rally, the original purpose of which was to discuss the Arab–Israeli conflict. Several people spoke; then, Michael Lerner ceded the Free Speech platform to ASUC Student Body President Dan Siegel because students were concerned about the fencing-off and destruction of the park. Siegel said later that he never intended to precipitate a riot; however, when he shouted “Let’s take the park!,” police turned off the sound system. The crowd responded spontaneously, moving down Telegraph Avenue toward People’s Park chanting, “We want the park!”

Arriving in the early afternoon, protesters were met by the remaining 159 Berkeley and university police officers assigned to guard the fenced-off park site. The protesters opened a fire hydrant, several hundred protesters attempted to tear down the fence and threw bottles, rocks, and bricks at the officers, and then the officers fired tear gas canisters. A major confrontation ensued between police and the crowd, which grew to 4,000. Initial attempts by the police to disperse the protesters were not successful, and more officers were called in from surrounding cities. At least one car was set on fire. A large group of protesters confronted a small group of sheriff’s deputies who turned and ran. The crowd of protesters let out a cheer and briefly chased after them until the sheriff’s deputies ran into a used car facility. The crowd then turned around and ran back to a patrol car which they then overturned and set on fire.

The use of shotguns with buckshot

Reagan’s Chief of Staff, Edwin Meese III, a former district attorney from Alameda County, had established a reputation for firm opposition to those protesting the Vietnam War at the Oakland Induction Center and elsewhere. Meese assumed responsibility for the governmental response to the People’s Park protest, and he called in the Alameda County Sheriff‘s deputies, which brought the total police presence to 791 officers from various jurisdictions.

Under Meese’s direction, police were permitted to use whatever methods they chose against the crowds, which had swelled to approximately 6,000 people. Officers in full riot gear (helmets, shields, and gas masks) obscured their badges to avoid being identified and headed into the crowds with nightsticks swinging.

As the protesters retreated, the Alameda County Sheriff’s deputies pursued them several blocks down Telegraph Avenue as far as Willard Junior High School at Derby Street, firing tear gas canisters and “00” buckshot at the crowd’s backs as they fled.

Authorities initially claimed that only birdshot had been used as shotgun ammunition. When physicians provided “00” pellets removed from the wounded as evidence that buckshot had been used, Sheriff Frank Madigan of Alameda County justified the use of shotguns loaded with lethal buckshot by stating, “The choice was essentially this: to use shotguns—because we didn’t have the available manpower—or retreat and abandon the City of Berkeley to the mob.” Sheriff Madigan did admit, however, that some of his deputies (many of whom were Vietnam War veterans) had been overly aggressive in their pursuit of the protesters, acting “as though they were Viet Cong.”

Reagan defended his decision to use the California National Guard to quell Berkeley protests: “If it takes a bloodbath, let’s get it over with. No more appeasement.”